Saturday, April 19, 2025

Godzilla vs. Hulk

Thursday, April 17, 2025

'Enormous Radio' is parable for our socially saturated age

The Westcotts overheard that evening a monologue on salmon fishing in Canada, a bridge game, running comments on home movies of what had apparently been a fortnight at Sea Island, and a bitter family quarrel about an overdraft at the bank. They turned off their radio at midnight and went to bed, weak with laughter.

But soon, Irene finds herself obsessed by these clandestine peeks into her neighbors' lives and can no longer maintain a polite facade of ignorance in public. The listening becomes a daily ritual:

Irene shifted the control and invaded the privacy of several breakfast tables. She overheard demonstrations of indigestion, carnal love, abysmal vanity, faith, and despair. Irene's life was nearly as simple and sheltered as it appeared to be, and the forthright and sometimes brutal language that came from the loudspeaker that morning astonished and troubled her. She continued to listen until her maid came in. Then she turned off the radio quickly, since this insight, she realized, was a furtive one.

One day, Jim comes home to his wife's insistence that he go to a neighboring apartment and stop an abusive husband. Instead, he turns off the radio, scolds her for eavesdropping, and has a repairman fix the device the next morning. (No word on how the repairman reacts to a device that can spy on one's neighbors.)

But the damage has been done. As a colleague recently observed about a sensitive situation in the workplace, "Once you know, you know, and you can't ever not know again." Irene has peered behind society's curtain and found a humbug. Her faith in humanity cannot be restored. Nor can she return to that blissful state of unknowing.

But Cheever saves one last revelation. Irene, the reader learns, is not as innocent as she appears to be, and in her own past, there are circumstances, decisions, and declarations just as petty, sordid, and shocking as anything blaring through the enormous radio.

One of the themes of Cheever's story is the disquieting nature of moving from innocence to knowledge, wherever and however this happens. Parallel to this runs a moral for our oversharing, social media era, where all of us listen to the enormous radios of Facebook, X, Instagram, and more. The revelations there threaten to change forever how we view neighbors, family, and friends.

What's worse is that so many of us—myself included—willingly speak into our enormous radios, sharing and oversharing, commenting incessantly with words we would be too timid to use face to face.

Yet despite these revelations, or because of them, social media goes on and on, confidently infiltrating our lives, monetizing our shared secrets and shattered expectations, providing a mechanism by which we trust others less and build walls at the very time when we should be doing the opposite.

At the end of "The Enormous Radio," Irene "held her hand on the switch before she extinguished the music and the voices, hoping that the instrument might speak to her kindly."

Instead, the announcer brings the news of twenty-nine dead in Tokyo, followed by the weather. She—and we—can do nothing to effect change in either.

The YouTube link at the top of the page is a wonderful CBS Radio Workshop adaptation of "The Enormous Radio." It's worth a listen. You can find Cheever's original story here.

Wednesday, April 16, 2025

The Unexpected No. 202

I wasn't buying many comics for myself in 1980, so I don't know if this issue was a gift or if I picked it out. It could have been one of a handful of comics that showed up in my Easter basket that year, although the cover likely would have given my parents pause.

Despite that nightmare-inducing rabbit, the scariest part of Luis Dominguez's illusration is the kid in the orange-and-yellow shirt. Those thick eyebrows reek of menace, and if little Yellow Dress had to choose between him and the giant bunny, she might have done better with the rabbit.

The interior of the book is standard anthology fare for DC at the time. Abel, caretaker of the House of Secrets, introduces the stories, most of which are written and drawn by unknowns. The two exceptions are "The Midnight Messenger," with the great Joe Orlando joining Ken Landgraf on art, and the cover story.

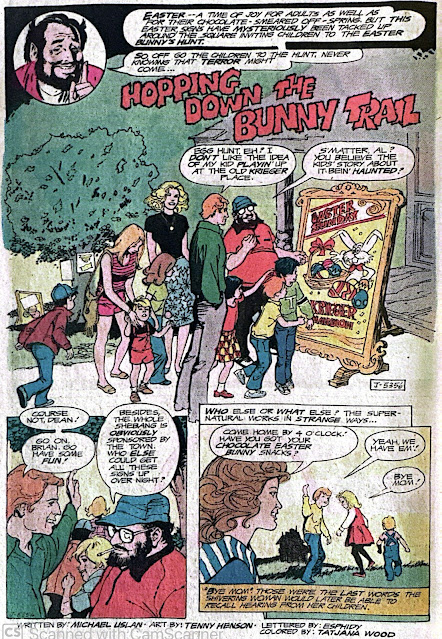

"Hopping Down the Bunny Trail" is written by Michael Uslan of Batman movie-producing and Shadow fame. It's drawn by Tenny Henson, lettered by Esphidy, and colored by Tatjana Wood (who colored oodles of DC stories and covers).

The story opens with two staples of such tales—the creepy old house and the too-trusting parents, who have no problem with an egg hunt at the local haunted emporium, provided it gets the rugrats out of their lives for a little bit.

Two panels later, the kids arrive at the gates of the old Krieger place (apparently, it's bad form not to speak of its age with each reference) and meet the giant rabbit at the gates. The bunny just has to be "Old Man Snyder" (everything in this town is old, apparently) because "he always dresses up as Santa Claus at Christmas time."

So off the three little cherubs go on their Easter adventure, locating more eggs inside the spooky old mansion than their peers, thereby winning the "big toy" that the talking rabbit—who, as we will learn, is most assuredly not Old Man Snyder—promised.

Before the reader can say "plastic grass," the kids have fallen through a trap door and into a vat of chocolate, as children are wont to do. This is when the perfidy of Peter Rabbit makes itself known. The bunny is hungry, and can you guess the main course?

In the penultimate panel, the life-sized rabbit looks to pull little Marvin headfirst into his (its?) mouth. To underscore the irony, the narrator tells us that all his two friends can see is "the object that dropped from Marvin's pocket—his chocolate Easter bunny with the head bitten off!"

I have to credit Henson for capturing the horror of what could have been a silly moment. The rabbit is disturbing, maybe because we don't know at first if it's real or just Old Man Snyder dressed up in a costume and revealing his homicidal (and canibalistic) tendencies. And he would have gotten away with it, if not for those darn kids!

Five pages of brutal simplicity are on display. Setup, escalating tension, climax, and decapitating denouement are all efficiently, uh, dispatched.

It doesn't appear that this story will be reprinted in the upcoming DC Finest volume, The Devil's Doorway, which is a pity. There aren't all that many Easter-themed horror stories, and this one makes quite an impression.

Tuesday, April 15, 2025

ROM Omnibus Vol. 1

I was recently a guest writer at the Collected Editions blogsite, reviewing ROM Omnibus volume 1. Here's a link.

Monday, April 14, 2025

Sunrise on the Reaping

The book tells the story of Haymitch Abernathy, the drunken mentor of Katniss Everdeen, District 12's most famous victor of the annual Hunger Games. Similar in some respects to President Snow's backstory from The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes (2020), Haymitch's adventures begin with the love of a young woman from the Covey, that group of traveling musicians living on the outskirts of the district, both literally and figuratively.

Abernathy breathes a sigh of relief on the day of Reaping when his name is not called, meaning he can continue his life as a bootlegger-in-training and helper to his mother and little sister. But the relief is short-lived as Capitol incompetence leads to Abernathy being named a substitute, sent off with three other young people on an adventure only one can survive.

From this point, the novel follows an enjoyable, if predictable, trajectory: Abernathy and his fellow tributes are shuttled off to the Capitol, trained in various forms of woodcraft and fighting techniques, and eventually dropped into the Arena, the high-tech environment where they will battle to the death.

Sunrise on the Reaping reminded me of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, not in any plot sense but because both feel like soft reboots of earlier versions of their respective series. While Sunrise hurtles along at a lively clip, especially once the characters begin to compete in the Hunger Games, it is also an exercise in déjà vu. Many scenes, inventive though they are, serve as callbacks to earlier moments (or, technically, later ones, as this is a prequel). This entry is not as original or as compelling as Songbirds and Snakes, which had the difficult task of balancing the characteristics that led Snow to villainy with some redeeming qualities to allow the audience to sympathize with him.

Haymitch is a compelling character who is easy to root for. In keeping with the hangdog, down-on-his-luck persona established in the earlier books, the prequel Haymitch is the victim of almost preternaturally bad luck. Some of this he brings upon himself, but much is just a matter of unfortunate circumstances. As if being chosen for a slaughter-or-be-slaughtered scenario could ever be viewed as fortuitous.

Collins is a sensitive writer, so the dialogue rings true for the world she has now invested five books in developing. She deepens the mythology while avoiding too many overt references to the other novels and characters. The various observations about how a state-run media can shape a story through selective editing are especially welcome—and timely.

It's worth noting how Collins has used the plot kernel of people hunting people, a staple of pulp fiction as far back as Richard Connell's "Most Dangerous Game," (arguably the story more freely adapted than any other for radio, TV, movies, and other stories/novels), given it a dystopian sci-fi twist, and built an increasingly rich world around it.

Wednesday, April 9, 2025

Spy vs Spy: The Big Blast

The newsstand collections of classic MAD material may fly below the radar of some fans, but I enjoy them. Whether this enjoyment extends beyond flipping through the pages to actually buying them ... well, not always. Still, I couldn't resist plunking down my hard-earned shekels for Spy vs. Spy: The Big Blast. Even though, at $14.99, it is assuredly not cheap, to paraphrase the omnipresent advisory from past Mad covers.

The world of Antonio Prohias' black-and-white battlers is visually dense. These strips cannot be scanned casually. The reader must peer into them to determine Messrs. Dark and Light's antics and how their shenanigans pay off in the final panel.

It took me a few minutes to adjust because it's been many years since I last perused the characters. Let's say I had to clean my spyglasses. Take, for instance, the first strip reprinted in this volume, from Mad #74 (October 1962):

One first notices the presence of a female spy, who often outwits both men, as the wrecking-ball gag in the top half of the page demonstrates. This single panel is much larger than the ones below and thus easier to decipher.

In the gag at the bottom of the page, I'm ashamed at how long it took me to figure out that the female spy is dropping objects into the sleeping spies' upside-down hats and not into lampshades or ashtrays. And this is with the images reproduced in color, presumably making it easier to discern the headwear.

(A word about this volume and color: Editor John Ficarra notes his dream is to colorize all the Spy adventures. This is "despite the fact that the entire strip was predicated on the literal dichotomy between 'Black' and 'White,'" he writes. While Ficarra characterizes the coloring as a universal good (calling S v. S one of the "clear winners" of the editorial decision to print the magazine in color starting in the year 2000), I'm not so sure. The stark contrast may have made it easier for readers to notice details like the above-mentioned hat trick. Coloring, especially on strips that share space with the one-panel gags, obscures the stage business that sets up the punchline.

And those punchlines, despite their variety, are all of a piece. One spy or the other gets crushed, creamed, jolted, jilted, or annihilated, except in the early strips where both sometimes do. It's similar to watching a Road Runner cartoon—the viewer knows the Coyote is always going to get his, so the fun is in how the schemes unravel for him this time.

Later strips in the Spy vs. Spy collection, where Prohias gives himself an entire page for continuity—or perhaps he is given the room (not sure how much freedom he had in this regard), work better. The larger size (see below, from October 1970) makes the business easier to follow.

Mad has made this collection more appealing by featuring the work of Peter Kuper, who started drawing the Spy vs. Spy strip in 1997. His two-page spreads allow for much more panel innovation. Also, his strips are bloodier, as seen in the punchline to the July 2001 strip below. I prefer Kuper, as sacriligioius as this admission may be. Please don't put dynamite in my dresser while I sleep.

Monday, April 7, 2025

Godzilla vs. Fantastic Four

Anybody who knows how much I love comics also knows how much I wear my heart on my sleeve where the Marvel Comics' series Godzilla King of the Monsters is concerned. It's easily the best series of my youth and firmly in my top-five favorite series ever.

So I was excited to see the original 24 issues reprinted last year in a deluxe hardcover edition and even more excited to learn of a new six-issue series featuring Godzilla and some of the luminaries in Marvel's stable. The first of these is Godzilla vs. Fantastic Four. (Spoilers ahead!)

First, it's obvious the creators went all-in to make Godzilla an integral part of the Marvel Universe, in much the same way that DC did last year with Justice League vs. Godzilla vs. Kong. This issue includes not just the Big G and Marvel's cosmic-powered quartet, but also Silver Surfer, King Ghidorah, and even a cameo by Galactus.

The story takes place shortly after Godzilla's first movie appearance. Readers learn very early (page one, panel two, as a matter of fact) that the Fantastic Four tried to help Tokyo during that initial cinematic encounter but arrived too late. Now Godzilla is back, attacking New York City, so Reed, Sue, Ben, and Johnny have a second chance.

This scenario sets the stage for an issue that is almost entirely action, exactly what most readers want from a pairing of these properties. An added wrinkle comes from the news that King Ghidorah, the three-headed hydra from Toho Productions, is the new herald of Galactus. Thus, it will require the combined might of the FF and the Silver Surfer, Galactus's former herald, to stop him.

The story goes down smooth and is fun to read. Writer Ryan North has captured the dynamics of the FF's relationships during the Silver Age—the uber-intellectual Reed, the bantering Johnny/Ben dynamic—while modernizing Sue Storm to make her far more capable than she ever was in the early years of the strip.

One big caveat—and it may be more a matter of editorial dictate than a flaw in North's script—is that nothing in the story makes it abundantly clear this is all happening in the past. Maybe Marvel doesn't want to call attention to the age of its most popular properties, maybe the powers-that-be thought a story spread across six decades would lose dramatic immediacy, or maybe the whole story-across-decades idea is meant to be more of an Easter Egg than a bonafide plot point.

However, the only real indication I had about the timeframes being adjusted from issue to issue came from the house ad on the back cover: "Godzilla takes on the Marvel Universe across the eras!" The story itself takes a far more subtle approach: the bathtub-shaped Fantasticar and Sue's hairstyle are tipoffs that this isn't happening in contemporary continuity, but it wasn't until a reference by Ben to the Silver Surfer being exiled to Earth that I really figured out the timeframe. (Maybe I'm dense, too—always a possibility.)

Part of the problem is the artwork. It's fashionable in some quarters to slam John Romita Jr., and that's not what I'm doing here. He's a great artist, and pairing him this issue with inker Scott Hanna makes for some clean, easy-to-follow artwork. However, nothing about the visuals screams Silver or Bronze age. Sadly, not many artists from this period are still alive and/or working, so the best readers can hope for is art that replicates that past glory. And this issue, as fun as it is to look at, simply doesn't capture that era.

Regardless, I'm onboard for all six issues. Here's hoping for a bombastic battle between Godzilla and the Hulk later in April!

Sunday, April 6, 2025

Batman's Strangest Cases

Unlike my previous tabloid-sized purchase, Batman's Strangest Cases wasn't part of my childhood collection. I had never heard of the book until DC reprinted it in March.

The moody cover—"moody" if you consider comic book pages blowing across a darkened urban landscape to be sinister, I guess—promises "The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Published," a bit of hyperbole considering all five of the stories contained within were relatively new when this collection was released in 1978. Unusual for the time, the creators are listed out front, and it is a murderer's row of talent: Denny O'Neil (who writes three of the stories), Neal Adams, Len Wein, Bernie Wrightson, Frank Robbins, Dick Giordano, and Irv Novick. How recognizable these names were to newsstand patrons of the time is unknown.

The stories are all Bronze-Age fun, situated in the period where Batman was receiving the serious treatment by DC, but before he became the grim-and-gritty poster-child of the late 1980s to today.

My favorite story in the volume is the first, "Red Water Crimson Death," a team-up of sorts between the Dark Knight and Cain, host of DC's long-running House of Mystery anthology series. The latter stays in character throughout, breaking the fourth wall to narrate and offer sly asides to the audience, thus eschewing the caption boxes so prevalent in most mainstream titles of the time. It's an exciting tale that takes Batman from the mean streets of Gotham to the shores of Scotland for a real gothic-inspired mystery.

The second story is the oft-reprinted first meeting between Batman and Swamp Thing, from the seventh issue of Swampy's own book. The moody artwork by Wrightson is the main draw here (no pun intended), as I found the story didn't age as well as I thought it would. The visual of Swamp Thing in a yellow trenchcoat and fedora evokes memories of the golden age of detectives, which even in the 1970s was fading fast. A house ad at the end of the story promotes the second issue of The Original Swamp Thing Saga, a series of reprints that were my initial introduction to Len Wein and Wrightson's classic series. The wraparound cover depicts Swampy's battle with the Frankenstein Monster and Werewolf surrogates from issues three and four.

The third story in Batman's Strangest Cases is "The Batman Nobody Knows." According to the opening caption box, "three ghetto-hardened kids" have joined Bruce Wayne on a camping expedition in the woods, a scenario that in our jaded twenty-first century feels suspect on its very face. The kids each share their impressions of Batman as crimefighter, supernatural force, etc., culminating in an appearance by the real deal, whom the kids write off as Bruce Wayne in a not-so-impressive costume. A funny little short, this one serves as a segue into the final two tales, both of which are fairly oozing with gothic trappings.

In "The Demon of Gothos Mansion," our hero sets out to help Alfred Pennyworth's niece, who has taken a teaching job at a desolate estate "one hundred miles from the nearest town." Little does she—or Batman—know that she has been recruited to help bring to life a demon, Ballk, at the cost of her own life. Batman ingeniously escapes a death trap. More escapades ensue.

The final entry, "A Vow from the Grave," involves a group of displaced circus performers (what we'd once uncharitably characterize as "freaks") and an escaped murderer. As with all the stories in this volume illustrated by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano, this one is saturated—almost literally, given the incessant rainfall—with atmosphere, making them great candidates for the giant-sized treatment in this volume.

One refreshing aspect of all the stories is the way Batman is portrayed as fallible, albeit within the boundaries of pulpish fiction. In other words, he's a trained fighter who will come out on top by the end of every adventure (this is never in doubt), but he is by no means invincible. In "Red Water Crimson Death," a loose step leads a common thug to get the jump on him, causing Commissioner Gordon to insist that our hero go on a vacation. "You're no good to me dead!" Gordon exclaims.

Similarly, Batman looks like he's putting in some effort to dispatch bad guys on a dock in the Swamp Thing story, while O'Neil sees fit to add a caption in "The Demon of Gothos Mansion" to explain how Batman's defeat of two country thugs, armed with a sycthe and axe, is possible only because of "long years" of training. In Batman stories of the last few decades, such victories are treated as foregone conclusions, and our hero would never be tripped up by something as mundane as a loose step. The character is poorer for being divorced from his roots as a regular person in a costume and elevated to near-deity status in today's comics and films.

A final observation is how much narrative ground can be covered so quickly in these stories. It takes exactly one page of story to get Bruce Wayne from Gotham City to a secluded country estate in "The Demon of Gothos Mansion," an entire story that, in 15 pages, is a marvel of economy. Similar efficiency is evidenced in "A Vow from the Grave," which has the same truncated page count. I know it's Old Man Shouts at Cloud territory to bitch about decompression in modern comics—and, listen, I love a lot of modern books—but it's so refreshing to read a complete story in just one sitting.

Overall, I really enjoyed Batman's Strangest Cases, three of which were brand-new to me. For $14.99, it was a fun stroll through the Bronze Age.